Dear friends,

It’s November 1, the traditional beginning of the holiday avoidance season. It’s the time of year when I program-out the local radio stations (not listening to you, Mix96) that switched to the 24/7 Christmas music today and the big box retailers who have declared that November 1 is Black Friday. (Looking at you, Kohls.) I will, with all my might, avoid their tinsel-festooned commercial caverns all of this month, and as much of next as I might.

That’s not because I dislike the year-end holidays. No, quite to the contrary: I’ve always embraced the communal spirit of celebration, the defiance of the cold winter nights and the opportunity to take a moment to remember to be grateful for one another. This dogged insistence on flogging holiday sales months in advance of the events does nothing but drain away any sense of the specialness, sacred or civil, that those few mid-winter nights once offered.

Thoughts after my AAII Conference sojourn

Thanks to the folks at AAII for inviting me to speak at their annual conference, this year in Orlando. Going from 40 and breezy in Iowa to 90, humid, with thunderstorms and scamper-y, mouse-sized lizards in Florida was a bit much for my system.

Thanks to the folks at AAII for inviting me to speak at their annual conference, this year in Orlando. Going from 40 and breezy in Iowa to 90, humid, with thunderstorms and scamper-y, mouse-sized lizards in Florida was a bit much for my system.

They are, Chip tells me, “anoles.” I mostly nodded and prayed they’d stay out from underfoot.

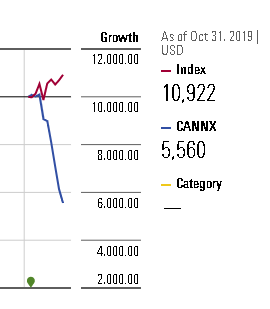

For those interested, the title of my talk was “The Indolent Investor: Managing Long-Term Decisions in a Sea of Short-Term Noise.” I tried to broaden my listeners’ understanding of the media universe that surrounds them, its effects on their own (investing and other) behavior and the strategies for managing it. The quick summary of the problem looked like this:

I suggested three sets of strategies: insulating ourselves from the noise, inoculating ourselves against the worst sorts of stories, and aligning our portfolios with long-term needs rather than short-term reactions. I’ll happily share the specifics with anyone interested.

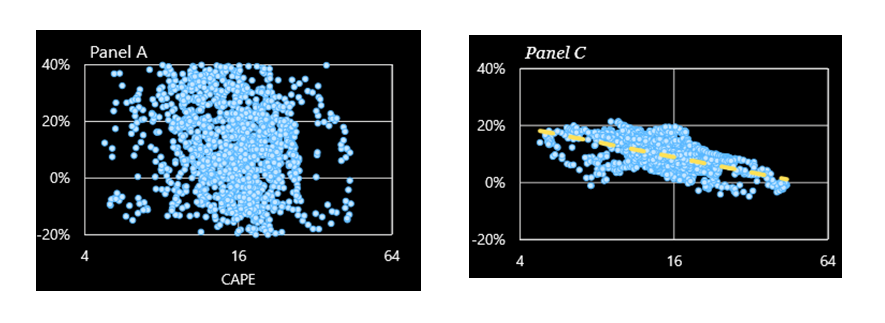

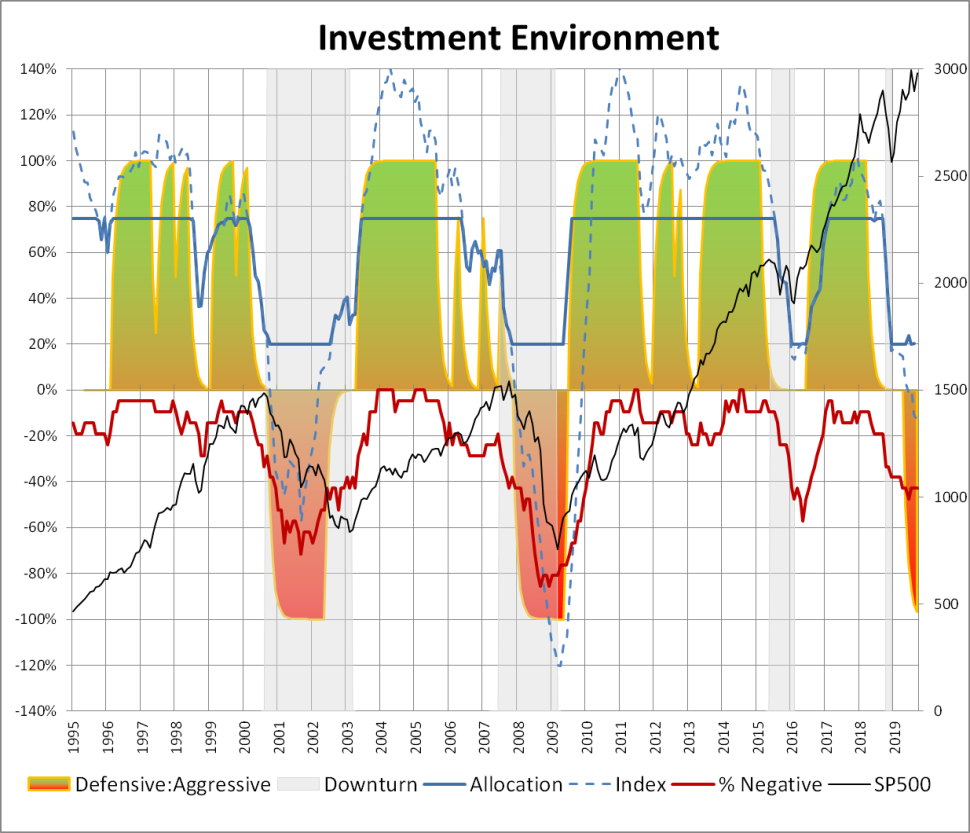

The talk gave me the opportunity to share one of my favorite graphics, from a powerful and readily-accessible presentation by Rob Arnott. His point is that valuation matters in the long-run. A lot. Really, it matters more than anything. Here’s the graphic:

What you’re looking at is the relationship between what you pay for stocks (the CAPE p/e, along the bottom) and how much you make from stocks. Panel A shows the relationship after one year. More properly, the lack of relationship after one year. It’s clear that you sometimes buy a cheap market and, a year later, have lost a mint; those are the dots in the lower left of Panel A. Sometimes you buy into an egregiously overvalued market and, a year later, have made a mint; that’s the 40% gain dot in the upper right. In the short term, price doesn’t matter.

But in the long term? That’s Panel C, which shows your returns after 10 years. In that time frame, there’s a clear, evident and consistent pattern. The dashed yellow line represents the average return at each price point. If you pay 52 p/e (Amazon’s current rate, fyi) for a basket of stocks, after 10 years you’ll have made zero on average and below zero (for 10 years!) frequently. Our current Shiller CAPE p/e is 30, which is not a pretty portent.

Rupal Bhansali impressed me. We had a thoughtful, though brief, conversation about the evolution of her funds and her take on the market. Roughly, she’s attracted billions in institutional money but a tiny fraction of that from retail investors. And, given her insistence on investing only in sound businesses and discounted prices, she estimates that her investable universe has shrunk to about 5% of the market. That’s caused her to trim the number of positions in her portfolios, though she remains almost fully invested.

James O’Shaughnessy impressed me. His keynote address was funny and wide-ranging, and started from the premise “we are all descended from cowards.” His point is that, in an evolutionary sense, “the fight or flight reaction” worked best as “the flight reaction” because bold and fearless aboriginals generally got eaten before achieving parenthood. Instinctive risk aversion, he argued, cannot be educated away. His solution was reliance on quantitative models which knew no fear, and that’s the direction his firm has gone. My own reaction is that quant models are one possibility, but only one and quite often as flawed as the humans they supplant. (Quant funds, as it turns out, work pretty poorly in falling markets, as do the rest of us.)

Mebane Faber did not impress me, at least not positively. Manager of the Cambria ETFs, he came across as arrogant, disrespectful, full of unconditional declarations and easy generalization, and largely lacking in self-reflection. I left about halfway through, and was not the first to depart.

The FINRA representatives asked if I would mention to you the existence of their Fund Analyzer. They seem rather proud of it for its ability to do side-by-side comparisons of fund and ETF expenses. FINRA is the industry’s Congressionally-authorized self-regulatory scheme. Folks on the MFO discussion argue that FINRA, like most self-regulators, is forced into a series of compromises that belie the celebratory rhetoric.

Since I’m mentioning tools, the folks at As You Sow offer a simple tool for identifying funds with high scores on four hot button issues: carbon-free funds, gun-free funds, deforestation-free funds (who knew?) and gender equality funds. Since sorting through the increasingly mountain of ESG-come-lately funds is getting tougher and tougher, they seem to be offering a useful service.

Morningstar’s challenges

If you’ve had difficulty using Morningstar’s fund tools, or even accessing them, you’re not alone. One of the longest recent threads on MFO’s discussion board is entitled “Morningstar is falling apart.” The complaints raised there echo my own experience and I’ve spent a lot of time in recent weeks trying to work things through with Retail Support (aka “Joe”). For example, I tried to chart the total return of the Voya Corporate Leaders Trust (LEXCX) against the DJIA from the fund’s 1935 inception. Nine or ten emails later, that turns out to be impossible. The evident option in their chart only tracks the Dow for nine years. With the intervention of the media relations folks and the Morningstar Direct folks, I got closer to an answer which is the indexes have sort of secret internal codes. If you know the codes, you can get close to the answer but it’s not necessarily possible to find the code.

A pending discussion asks how it’s possible for a fund to simultaneously be in the top 32% of its peer group for a particular year and trail the peer average. The response simply explained to me what 32% meant.

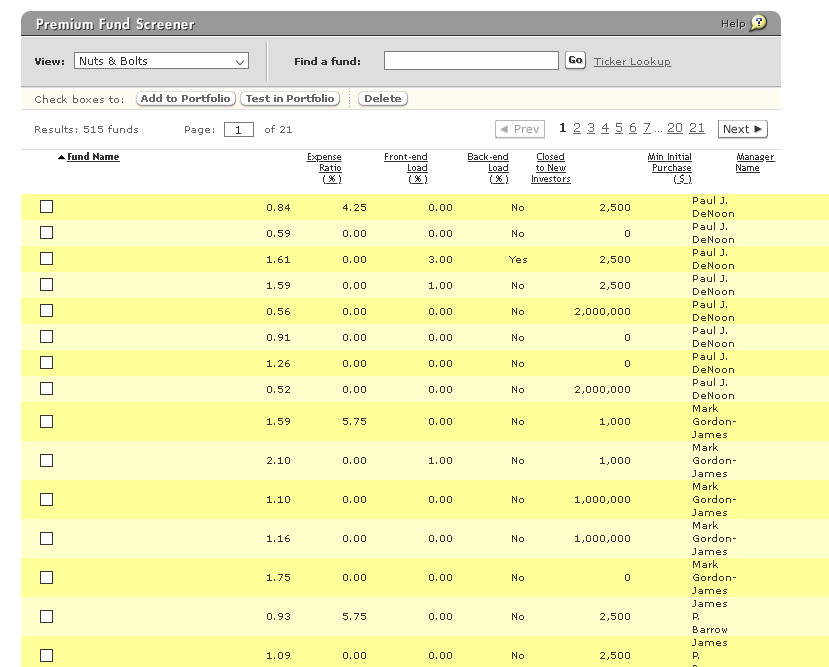

Our most dramatic discussion surrounds this image:

The Premium Fund search was willing to give me what I asked for, as long as what I asked for didn’t include the names of any funds. The folks in Morningstar media relations confirmed the difficulty and got back quickly with the message that the screener might be functioning again in the middle of next week. (sigh)

Even folks with access to Morningstar Direct, the high-end professional product, are complaining that they’ve lost access to data they could once easily retrieve.

I mention all of that for two reasons. First, if you’re having trouble and doubting your sanity, set your mind at rest. Second, if you’re having trouble, reach out to Morningstar. They’re running a tremendously complicated operation, and they’re doing it in the context of a parent corporation whose priorities are … uh, evolving. They are trying to do a good job for as many people as their knowledge and resources permit, while surely under pressure to support the corporation’s earnings. Letting them know, clearly and politely, what’s not working is our best option for encouraging changes that keep the system alive.

The $2500 solution

We all know we need “an emergency fund,” that ill-defined pot of money designed to help us surmount … well, an emergency. The problem is that no one seems ever to have figured out what “an emergency” looks like or how much it plausibly costs. That gave rise to rules of thumb that seemed designed to discourage anyone from even trying to establish such a fund, since they’d never reach the “six months’ worth of expenses” threshold.

Why six months? Because it’s the rule.

Turns out there’s a far more reassuring answer than that, one grounded in empirical analysis. Economists from the University of Colorado and Diego Portales University in Chile looked at 70,274 low-income households across the country and concluded that lower-income households would be quite fine with an emergency account of $2,467. They found that emergencies costing $500 dollars are surprisingly common, but those costing $5000 are surprisingly rare. As they chart out the frequency of emergencies by the dollar-size of them, you get a graph that goes flat at about $2500. That means that $6000 is not much more helpful, in practical terms, than $2500 is.

A decent non-technical walk-through of their research is here, while the original, downloadable research paper is here. NPR, being NPR, did a nice job of placing the research in its larger context.

My own emergency fund consists of a modest insured savings account (paying almost nothing) and a rather larger investment in RiverPark Short Term High Yield (RPHYX), an exceptional fund only open to those purchasing through the adviser. For folks like me who can tolerate some variation in share price, Zeo Short Duration Income (ZEOIX) and PIMCO Enhanced Short Maturity Active ETF (MINT) offer something like 3% returns with minimal downside.

Thanks, as ever …

Thanks to Kevin, Philip of Bloomfield Hills, and our cadre of loyal Paypal subscribers Greg, Doug, David, Sheshadri, Brian, William, Matthew, and the other William. Special thanks to our newest Paypal subscriber, James!

In answer to your questions: we do have a summary of how all of the funds we’ve profiled have done. It’s our monthly Dashboard, a free resource hosted at the MFO Premium site. And I’m still working on how to include brokerage availability in each of our fund profiles. Formerly that was something that Morningstar collated, but they’ve dropped that service from their website. I’m looking for a reliable alternative.

Finally, I’d urge everyone to read Charles’s piece this month, on changes at MFO Premium. The power of the tools on that site has grown exponentially over the past five years and the cost of the data feed that drives it has risen over 20%. As a result, we’ve increased the threshold for gaining access to the MFO Premium site from $100 to $120. We believe that the tools offer great potential and are, relative to any comparable service, a great value.

If you would like to contribute and gain access to MFO Premium, please use the MFO Premium link. Likewise, if you’d like to send a check and gain access to MFO Premium, please note that on the memo line and share your email address with us.

The Mutual Fund Observer itself is, and always will be, a free, non-commercial, reader-supported public service. Your contributions, large and small, make it all possible. Folks who aren’t seeking MFO Premium access should continue to use our regular PayPal link, the one over there on the right.

Illness and a freak late October snowstorm threw plans a bit off-schedule this month, which means that our North Star Dividend and Yacktman Focus profiles will debut in our December issue, as will an update to our Akre Focus profile. Please join us for that, and much more, in the December – post-Thanksgiving, post Macy’s Parade, okay we can at least start talking about the holidays – Observer!

had in the past, which helps offset some of the truly aggressive holdings we still hold.

had in the past, which helps offset some of the truly aggressive holdings we still hold.

only a tiny bit less volatility. Harbor chose to empanel a new subadvisor, Cedar Street Asset Management. Cedar Street was founded in April of 2016, as an employee-owned investment management firm and has approximately $250 million in assets under management as of June 30, 2019.

only a tiny bit less volatility. Harbor chose to empanel a new subadvisor, Cedar Street Asset Management. Cedar Street was founded in April of 2016, as an employee-owned investment management firm and has approximately $250 million in assets under management as of June 30, 2019.